Gathering Plants for Cyanotypes at McConnell Lake Provincial Park

The first time I visited McConnell Lake was on a cold morning the first September after I moved to Kamloops. My friend Jenna, the type of person who wakes up at 4am and decides she needs to be in nature immediately, invited me to come with her and 20 minutes later we were driving up and out of the valley as the first flakes of snow I’d seen that year started falling.

I have a confession: I don’t inherently love the landscape that makes Kamloops so distinctive. I understand that the gentle rolling grasslands, grand vistas, and sepia tones are beautiful. There are times when I can see that beauty, especially in the spring when the sage is most green and the grass is like margerine spread across the hills. But it’s too subtle for my taste, and largely wasted on me.

I want to be overwhelmed by the colour green and the funk of wet earth in my nose. McConnell Lake does that for me, and since that first visit its become the place I’ve walked the most near Kamloops. It takes about an hour to walk around the lake, which is the perfect length of time for a walk in my opinion: long enough to feel like you’re doing something real, not so long that you can’t fit it in almost anytime. In the summer it’s significantly cooler than Kamloops, where daily highs are in the 30s. In the spring its one of the first trails to clear of snow and smell like forest. Its especially beautiful in the winter right after a big snowfall.

McConnell is also a diverse little pocket universe. On the west side its sunny where an area has been cleared for parking and picnic tables and there is a meadow that spreads out in increasingly dense layers of plants. As you walk south you find pussy willows and a small marsh filled with cattails. The long east side opposite the meadow is where you spend most of the walk, and is almost entirely shaded by pine and cedar. Darker, damper, and damaged by pine beetles, this side is home to mushrooms and bright green wolf lichen. Walking here in the fall with my partner, who is compelled to photograph every mushroom, can turn that hour-long walk into an afternoon.

Gathering

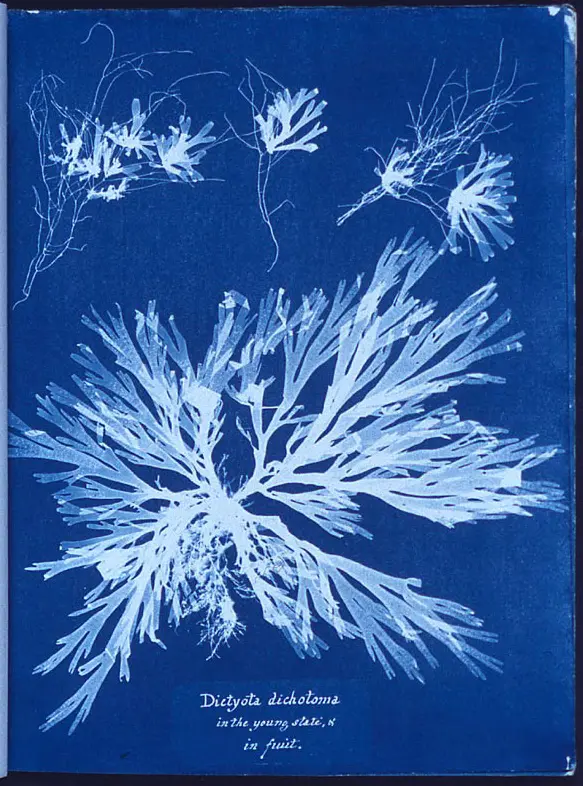

At the end of August my partner and I drove out to McConnell to gather plants so I could make cyanotype prints on some of the fabric I am going to use for my sabbatical. Cyanotypes use the sun to create dramatic blue prints. Originally used to make blueprints, I think they’re recognizable to most people when its used to make prints of plants.

I was hesitant at first, thinking too hard about what I was doing, trying to think my way through a feeling situation. I grew up in a rural community and remember gathering plants while on walks with my mom. Yet as an adult, this is all new to me, both as an actual thing-to-do and as an intellectual activity. I had struggled the previous couple months with what it means to do a research-creation project, to make something physical instead of a paper or program proposal. To make something personal.

Slowly I loosened up, following my eye and gathering what jumped out at me. I tried to collect mostly what was already dead: some dry thistles, a broken branch with clusters of grey pinecones, bone dry mushrooms, clumps of wolf lichen fallen onto the forest floor. The thistles pricked through the cloth reusable shopping bags we were using, extracting a blood price. The mushrooms smelled overwhelmingly earthy, a musky scent somewhere between bad and good, delicious and dangerous. The plants pulled from the lake smelled like wet animal, a smell which we had encountered earlier and made us think bear. Berries look like less than they should in a bag, a lesson I learn every time I pick them.

By the end we had two cloth shopping bags of materials and a 1/5 of a gallen bag of rose hips.

Back on campus we sorted what we had collected into what was already dry and what needed to be dried and pressed. We then found paper, boards, and clamps and spent an hour pressing the flowers and other plants between layers of paper and plywood that sat out with their legs in the air. Over the next couple weeks I returned to change the paper and eventually to start identifying, sorting, storing, and using them to make test cyanotype prints.

Time, Attention, and Meaning

I think I was so hesitant when I first started collecting because I expected to recognize and have feelings about more of the plants. After all, I had spent so much time out here, and I am doing a whole project about connections with nature. Instead, I found myself apparently as plant-blind as most people.

After, I was reminded that I did have meanings for many of these plants. I associate cattails with my partner because of the joy she gets splitting their dense seedpods open in the wind. Wolf lichen is so vibrant that it fills the need for “overwhelmingly green” even in the middle of winter. The mushrooms are something we come back to visit many times a year, just to see what they are up to.

And over the next couple months, as I worked with the plants—sorting them, drying them, changing the papers in the presses, re-sorting them, clipping them, giving them new homes, identifying them with iNaturalist, starting to make cyanotypes with them—I realized that it was this process and the time and attention that was helping me give the plants meaning. I don’t have strong feelings about them yet. They are the background to a place I love and have spent a lot of time with the people I love the most. But I know their names now, which ones press well, and which ones draw blood.